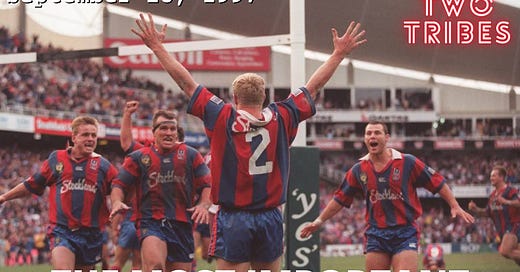

September 28, 1997: The most important grand final of all time

To mark this milestone, Two Tribes is released today as an ebook and we publish an extract about the Knights' mythical crusade.

Today’s the day: the 25th anniversary of the most important grand final of all time.

If you’ve read Two Tribes you’ll know why I describe Newcastle’s 22-16 win over Manly that way.

It was important even if you didn’t like the impact of its significance, even if you were a Super League devotee. It changed things irrevocably - whether you think it was for the better or for the worse.

That’s because in the months that followed, when News Limited held all the aces, the ARL could demonstrably say that the fans were in their corner, that the organic resonance of the sport was still theirs.

It gave them cards to play at the peace table.

To celebrate this momentous anniversary, we are releasing Two Tribes on Kindle today.

Follow these links:

BOOK EXTRACT: THE HOLY GRAIL

By STEVE MASCORD

Amid the confusion, uncertainty and widespread ambivalence towards onfield events, a cultural tidal wave was quietly gathering force up the F3 motorway from Sydney.

“It started when the finals started,” Knights chairman Michael Hill recalls. “There were 70 and 80 and 100 buses. The drama of the finals series and our progress through it was enhanced by the stories about the fans.”

Newcastle’s first appointment was Parramatta, on September 7 at the Sydney Football Stadium.

Knights assistant coach Steve Dunstan recalls: “As they drew into that finals series, you could feel the impetus of people getting behind the team. It was like this big wave of emotion. It started like a ripple and it just built up, built up.”

One of the Knights’ ball boys, Michael Maher, says now: “I was only 14 at the time but I was a passionate fan from the time they came in and I can remember some games they blew that year - they were not on other teams’ levels.

“They were never a chance against Manly. It looked like they were never gonna get over the top of them.”

With the peace process spluttering along, that DNA-level bond between sport and community - thought to be on the verge of extinction in rugby league after three years of rancour - suddenly exploded like nuclear fission.

The game’s innate ability to compensate for its many systemic flaws with transcendent moments was about to become incarnate once more, on an unprecedented and salvationary scale.

The Knights had two weeks previously trailed the Eels 18-0 only to run them down 28-20. In the hours before the Super League grand final, Knights winger Darren Albert then did the running down himself, stopping North Sydney’s Matt Seers with a tackle for the ages before Matthew Johns booted a field goal to end the Bears’ last real chance ever of a grand final appearance. The Novocastrians - driven to Phillip Street in a minibus to sign up with the ARL - were to play Manly, effectively the people who were doing the signing, in the second grand final of the split season.

“It was almost meant to be,” Knights doctor Peter McGeoch rhapsodises. “There are so many things that had to come together for us to win it. It was preordained, almost.”

But back in Steel City on Sunday September 21, there was a confrontation that exposed the dark matter inside the beam of light pointing the Knights towards immortality. The Mariners - still alive in the World Club Challenge - decided to pay the victorious ARL side a visit at a pub owned by Knights football manager Dave Morley.

“Things got a bit hectic, when Mal (Malcolm Reilly) and Sarge (Mark Sargent) looked like they were going to have an altercation,” recalls Dunstan.

“I don’t think it would have ever happened … but it was pretty close. I think it was more a little bit of adrenalin … having beers, everyone excited, made the grand final…

“There were a few of the Mariners boys who came down to pass on their support, I suppose. As a few beers flowed … Malcolm has a reputation of being a very tough guy and not suffering fools gladly.

“Someone only had to say something. It was always a very touchy situation.”

Paul ‘The Chief” Harragon separated ARL loyalist Reilly and Super League devotee Sargent in the toilets at Morley’s pub.

Dunstan stresses: “(But) in the whole season - and I was pretty close to him (Reilly) the whole year - he never once mentioned Super League. He never gave any indication it bothered him.”

Another Novocastrian tale would be played out in front of a much larger audience.

Andrew Johns had broken two ribs scoring a try against Parramatta. Despite receiving a painkilling injection before the preliminary final against the Bears, he had come off at halftime complaining of severe discomfort.

“He was breathing really fast,” McGeoch recalls.

“Oddly enough, I’d packed my bag and I ended up with all these quite long needles, which I wouldn’t normally have. I’d normally have a needle that was about 2cm long and these things were about 3cm long.

“He wanted a top-up and I’m actually topping it up with this needle I’m not entirely happy with. At some stage … I don’t think he actually registered that I’d done it and I don’t think I did either...

“We’ve done this and he’s gone to sit down on the other side of the room and I’m watching him and you could sort of see that he wasn’t quite right. He started looking in discomfort.

“Suddenly it’s dawned on me and I thought ‘oh fuck’.

“My life has flashed before my eyes. I’ve thought ‘oh fuck, we’re going to miss out on the grand final because of this. I’ve sat down, watched the second half with my heart in my mouth thinking there’s no way we can win without him.”

But they did, 17-12.

“And it’s just that combination of circumstances,” McGeoch continues. “I was absolutely ecstatic at the end of the game. I’ve never been at a game where I’ve ridden the highs and the lows so much.

“I thought ‘this is going to be terrible because there’s players who won’t ever get that opportunity again’ as a consequence of what happened.

“We got him into hospital and I think it was on the Monday he had the tube put in. He came out on the Wednesday. At the start of the week it was devastating - he’s gone into hospital! Maybe we’re thinking ‘fuck, maybe he will be able to play!’.”

Two days into grand final week, Whittaker invited reporters including me to Phillip Street and launched the National Rugby League Championship.

The structure allowed for an eight-man board - five from the NSW and Australian rugby leagues and three from News Ltd, which was designated only as “corporate partner”. The National Rugby League Championship would include up to 22 teams. “When News Ltd pulled out of talks, we thought about making public how far we’d come, so people could see what the roadblocks were,” Whittaker said. “But I have made a commitment not to discuss what happened in the talks. So we have gone one better - we have put it into practice.” Once more, it was stressed the new company would not take on the debt of Super League. News could appoint the CEO but he would be answerable to the NSWRL and ARL boards, not just News.

Yes, things were so bad the governing body willfully detracted from its own grand final week to promise the public a better future. Whittaker had a plan. He just didn’t know the degree to which fate would conspire to shake everyone out of their indifference and supercharge that plan.

That indifference, however, stopped at the Moonee Moonee Bridge as you headed out of Sydney.

In Newcastle, an afterthought for both sides initially, ‘extremist’ pro-ARL groups like Aussies For The ARL had been formed. They threw rocks through the windows of the Mariners with the same arm that held placards protesting the closure of the steelworks.

Newcastle was the only place that still really cared.

But the bubble around the Hunter region sometimes seemed physical to the Knights. “The last couple of weeks of the finals series,’ recalls Hill, “Ian Bonnette - the CEO … he and I drove down to see Neil Whittaker about getting some funds because the Knights were rooted.

“And we got to the Hawkesbury River and Neil said (by phone) ‘look, I can’t help you. I’m in a meeting, go home’.

“So we turned around and went home, won the final which no-one expected us to do, made a six-figure sum out of selling t-shirts as well as everything else we got and rescued the Knights financially.

“For the year ‘97, the Knights had no money at all.”

Opponents Manly - who’d been in the previous three grand finals - had won the last 11 games against their working class opponents.

Journalist Brett Keeble shadowed the Knights for grand final week. Like Hill, he didn’t particularly think of them as title contenders until well into September. He flew to Sydney with Reilly and Harragon on the Monday and travelled with the team on their bus again the night before the grand final breakfast.

“All they talked about was they felt a sense of destiny, they felt a sense that this is the time … ‘if we’re ever going to beat Manly, why not do it in a grand final?’

“You could feel the belief and the confidence growing within the team but rugby league players are confident before they go into any game.

“But the game itself? It was always a long shot.”

Newcastle’s coach was intimidating Englishman Reilly, a close friend of his opposite number, Manly’s Bob Fulton. "At the end of that season, he came up to Darwin for two weeks with myself and my sons and Royce Ayliffe and quite a few others,’ Fulton recalls in an interview for this book which was his last before he died on May 23, 2021.

Manly and Australia doctor Nathan Gibbs warned in the lead-up to the grand final at the Sydney Football Stadium Johns might die if he played. When I spoke to him, Fulton had no recollections to share of this iconic grand final week story.

But Gibbs told me: “Chippy (journalist Peter Frilingos) has rung me up. He’s saying ‘will he play next week?’ and I said ‘well a punctured lung, it depends how big it is, he might recover’.

“Then he’s saying ‘will he need a painkiller in his rib?’. I said ‘I’m not sure but he probably will. Obviously you should ask their doctor’.

“So he said ‘is it risky? You know, they’ve organised to have an accident/emergency physician on the sideline’. Chippy’s telling me this.

“I’m like ‘oh, they obviously have some concern about his ribs’. So he said ‘what could happen?’ and I said ‘he could get another punctured lung, it could increase’. ‘So what would happen?’

“I said ‘well he might have to come off and he might have trouble breathing’. Yeah, so what can happen with that? ‘Well sometimes it’s a tension in your thorax and sometimes you really have trouble breathing’.

“Well what can happen with that? Obviously you’ve got to release the pressure. ‘So what can happen?’ Well if you don’t release the pressure in time, it can stop the heart beat.

“‘And so what can happen?’ He could die.

“So that was the headline. The great Chippy, the great journo that he was, just hammered me and hammered me for 10 questions until I got to the .001 percent chance of sudden death - and that was the bit that was in the paper.”

Johns’ team-mate Marc Glanville says: “That was probably Bozo telling Nathan ‘mate to stir up a bit of that. Maybe it will unsettle Joey’. But he was going to play regardless.”

Michael Hill felt the comment from Gibbs was dirty pool. “The club said ‘that’s just everybody’s against us’. It was a typical Manly comment. It was just another piece of evidence that everyone was….”

Peter McGeoch: “Andrew enjoyed it. Subsequently when they’d go away on tour, he’d keep reminding Nathan of the quote. He’d come up and say ‘you might die Nathan’.”

Was it a conspiracy to put pressure on Johns?

“I was pretty media savvy by that stage in my career,” says Gibbs. “I knew what was going to be the headline if I said what I said. I was quite aware where it was going but at the time I felt it was quite funny. I enjoyed it and by that stage I knew Joey pretty well, we’d been on quite a few Origin and Australian trips away.

“And I’ve got to say, it’s quite impressive that he played with it. It was quite dangerous. There’s no doubt about it. You talk about the medical thing but it’s also performance. It’s bloody hard to play with a busted rib and a lung puncture because it’s pretty painful.”

Reilly, now 73, says of Johns: “Look, he had plenty of injections. How tough can you get? He was an inspirational person. Andrew was just a tough character. Single minded. Joey would have to be the best player I’ve ever been involved with, at any level.”

At one point in the finals, Reilly says, injury was giving Johns so much pain he wanted to come off. “I was on the bench and I said ‘mate, we can’t win this game without you, get back out there’ and he just turned around on a sixpence and went back out and got back into it.”

Harragon was also battling pain each week. “He did mostly pool work,” says Dunstan. “For a bloke who did that, his performances were phenomenal. He played State of Origin, he played Australia.

“His knees were bad, obviously. He was beyond reproach with his body. He sacrificed himself every game. He couldn’t recover enough to do any maintenance, running or ballwork.

“Adam MacDougall was basically the same. The last half of the season, Doogs was in pain as well. Doogs was carrying lots of injuries.

“The coaching staff made a decision in grand final week we didn’t have to do much other than a captain’s run because the state of adrenalin with the players was … we couldn’t train because guys couldn’t walk in the stadium, because there’d be a thousand people out front. Everyone wanted to be a part of it. Newcastle was going to be number one in Australia - and it was. It wasn’t only for a day. It was for a week, possibly a month. It was the number one city in Australia.

“When we were leaving on Saturday on the bus, they were three-wide up Lambton Road heading out to the highway.

“The tears and the emotion on that bus going down was phenomenal”.

Reilly’s team was hard and clever and fast but not without its rough edges. English hooker Lee Jackson, the coach admits, didn’t quite fit in. “He had one or two faults,” Reilly says. “He also had some qualities too. He was a good attacking player, his support play was good, he was quick. He could spot an opportunity.

“He didn’t mix. He wasn’t bothered about alcohol and his social skills weren’t the best in the world, mixing wise. I think that was seen as a bit of a detriment sometimes because the team loved a good time.”

‘Rivalry’ does not do the enmity between the sides justice. Maher once saw Manly’s trainers spray water all over their Knights rivals at Brookvale Oval - “even the Manly trainers would niggle the Knights trainers” - and heard the greatest hits of arch Sea Eagles sledgers Terry Hill and John Hopoate at close range. Hopoate, for instance, would call Darren Albert a “baby”.

Michael Hill: “On grand final day, buses came from Orange to Newcastle, from all over the country. They couldn’t get enough buses to take the people there. There was this great sea of people moving up and down the highway.

“People still tell me stories about where they were on grand final day. There was a bloke who said to me ‘I drove from Raymond Terrace to Belmont on that Sunday afternoon and didn’t pass another car’. The whole town was captured, absolutely captured.”

Two nights before the ARL grand final, the Australian Super League team was stunned 30-12 by New Zealand at North Harbour. On Sunday morning, the Sun-Herald ran a back page story announcing a 20-team competition in 1998. It said there would be “two conferences” with “regular crossovers” and a “Super Bowl.”

Andrew Johns wrote: “I remember the bus ride down to Sydney from Newcastle. It was so emotional seeing Chief (Paul Harragon) cry as the fans lined the streets to wish us well.

“When Chief called the team into his room the night before the game - no coach or officials, just the players - and went around the room and made every player explain what it meant to him to win the competition, the occasion hit home to all of us.

“I had an attitude of ‘whatever’ before the team meeting - I just wanted to let rip and play - but when Marc Glanville talked about how hard he had worked to come back from two knee reconstructions and how he’d battled (for) the club for 10 years and how this was the only grand final he was going to play and how much it meant to him, it really united us.

“I was really blown away by it because I thought these big moments happened all the time.”

The hotel was the Holiday Inn at Coogee. “Chief had got everyone around and said ‘let’s have a chat and go up to the room’ and we sort of said ‘no, we’ve had enough talks,” Glanville recounted when I interviewed him for Two Tribes, “and we’ve done everything’ and he said ‘no, no I think we should’ so we ended up going up there, just the players.

“Chief said when he was in the Origin team, one of the camps, Phil Gould got them all together and said ‘if this was your last-ever game of footy, what would you do to win it?’ or ‘what would it mean to you?’.

“We were going around the room and some of the young blokes were saying stuff and when it came to me … I hadn’t really thought about it much.

“When I started speaking, I thought ‘shit, this is my last ever game for the club, the club I’d been with for 10 years which is one third of my life’ … then, it was. And I hadn’t really achieved too much in the game. I had desires to play for NSW, play for Australia etc and unfortunately never did that.

“I spoke around ‘when I leave the game, I want to have achieved something and at this stage I haven’t really achieved anything’. Then I started getting emotional that it was my last ever game. I sort of broke down. I guess the younger guys, that meant something to them because they thought ‘shit he’s been there 10 years and played in the ARL for 15 years and this is his only grand final that he’s getting the chance to win’.

“I think that meant a bit for the younger blokes, that this is their only opportunity. They may never play in another one and there’s obviously been plenty of good footballers over the years who have never won a grand final.”

And so to game day. Windy, sunny, high teens, low 20s centigrade.

Hill: “There were only two types of people at that ground. There were Knights supporters and those who hoped Manly lost.

“We shouldn’t have got to the grand final but we got there and (John) Quayle sent out a message to all clubs, to the officials, saying ‘look, the NSWRL box is the NSWRL box and loud supporting and cheering for the teams is not appropriate’.

“I said ‘well shove it up your arse. I’ll watch the game out with my family’. So I didn’t go in the box. I knew who it was directed at because after we beat Norths we were just ecstatic.”

The Knights had taken extraordinary precautions against the possibility of Johns’ broken ribs and punctured lung rendering Nathan Gibbs’ predictions ghoulishing accurate.

“We had a cardio-thorasic surgeon called Alan Boyd who was a fairly keen supporter,” McGeoch recounts. “He got involved, it was fantastic. He put the tube in, got it taken out, gave (Johns) a stress test on the Thursday where he got him to do some work on the treadmill just to make sure that it was intact.

“Alan Boyd rang me after he did the stress test and said ‘there’s really no reason … look, there’s a bit of a risk but I’ll be down there and if we need to put a tube in, we’ll do it’.

“He actually came to the game. We were so grateful we gave him a signed jumper and I think he got 400 bucks (for it). He sat on the sideline for arguably one of the best games of all time, got a signed jumper and made a quid out of it. Every time I ran into him after that we had a bit of a giggle about how he had the best day in the world.”

Let’s stop there.

In one of the most famous games of all time, arguably the greatest player of all time could have needed emergency surgery at any time and had a surgeon sitting on the bench just in case.

Yep.

“Basically he would have put a tube in between the lung and the pleura space and taken the air out of it. You have a tube and a suction process. We didn’t put a percentage on it but we thought it was extremely unlikely to be necessary but in these circumstances you’ve got to cover all contingencies.

“It would be in the dressing room. There’s a thing called the tension in the thorax where the hole in the lung acts like a one-way valve. You’re pumping the air into a space and it’s not actually escaping and that can be a bit of a medical emergency.”

But no-one knew any anything but sketchy details of this outside the Knights’ inner sanctum as the teams ran onto the now-demolished SFS.

Maher: “When the Knights came out, it was as loud as Marathon Stadium. Maybe louder. When Manly came out, they got booed onto the field. In a grand final.”

Glanville: “Troy Fletcher had a great game and Chief, to start the game, coming out … The story goes that Mal Reilly had said to Chief, quietly, ‘no-one gets sent off in a grand final. Go out there and get into them’. We as a forward pack said ‘we need to get on top of them if we’re any chance to win’.”

By halftime, though, the working man’s team trailed 18-6. “It wasn’t looking good,” says Glanville. “It was quite funny, we were pretty relaxed even though we were trailing.

“When we all put our hands in together to say we were going to go back out there and give it our best, I think Butts (Tony Butterfield) or someone dropped a fart and Chief’s talking and we’ve all got our noses buried in our jumpers.

“We sort of broke up and laughed!”

And that afternoon at the Sydney Football Stadium, Joey didn’t die.

Instead, he set up a try for Albert in the dying seconds to win Newcastle their first premiership. “I reckon they might have got us if it went into overtime,” Johns wrote. “I hadn’t played much football. I was struggling to jog, let alone sprint.”

Andrew and his brother Matthew had studied tape of Manly - and other teams - leaving a gap behind the play-the-ball while defending with play near the sideline.

“I heard Matty calling for the ball, obviously for one last shot at field goal,” Andrew wrote. “I looked over from dummy half and there was John Hopoate staring at Matty and his body language showed he was going to charge out and jump Matty and try to charge the kick down.

“So I said to Darren Albert, who played the ball, “stay alive” and then feigned left and snuck down the short side to the right, dummied again to my old mate Mark Hughes on the right … then took the tackle of Craig Innes and put Alby in for the try.”

Fulton: “It was a grand final and every grand final, you've got to be prepared. It was the same as any grand final I've been involved in as a player and a coach.

"It was 16-all until Joey put that try on. The game goes for 80 minutes and there was a try scored in the last five minutes.”

Geoff Carr was high in the western stand at the SFS, with his eye on a prominent fan of his old club St George.

“It was generally my job, with security, to work out when the prime minister should go down to the presentation. It was accepted by security: probably seven or eight minutes before the end of the game because it was easier to get him down the steps at the old Sydney Football Stadium rather than wait for the lift because you could be stuck there a minute or two.

“John Howard it was. The idea was to get him down the steps before the crowd start to leave.

“There’s eight minutes to go and the security bloke’s looking at me and John’s really enjoying the game. It was a great game.

“I said to the security bloke ‘give it a couple more minutes because he’s really enjoying the game and I think it looks as if something’s going to happen’. It was one of those games that’s going to go to the wire but something’s going to break it open.

“Then with five minutes to go I sort of shrugged my shoulders and pointed to Howard. We’re sitting there. Then all of sudden there’s a couple of minutes to go and it wasn’t time to get up and go because he was going to miss it. We waited and as soon as Joey put him over, the security bloke said ‘we’ve got to go’ so we went

“And when we got to the steps there was nobody.

“Not a soul.

“Everyone was in the ground. No-one left. Not a person.”

The ARL allowed a small group of print media men out onto the field at full-time along with the radio and TV “sideline eyes”. One of my most vivid memories in 35 years as a journalist is being embraced by Matthew Johns in the middle of the Sydney Football Stadium after the most important grand final of all time.

Hill: “In fact, I gave an interview after the game out on the field. Craig Hamilton said to me ‘what do you think?’ and I said ‘we beat the fucking lot of them - the referees, the administration.”

Johns, meanwhile, told the ABC’s Hamilton: “I just want to get nude and sit on the goalposts”

Keeble recalls “Mal didn’t want to go on the lap of honour because he said it was for the players” and Reilly says: “After the game I had a bittersweet feeling to a degree. I just appreciated people on the other side … Arko had done so much for the game and Boze (Bob Fulton) … I’d been involved with the club before.

“But mate, I won two premierships with Manly, I won two with Castleford in England, I coached Great Britain beating Australia - very special - but that rates the very highest emotionally. The town was just immense in their support of the team and the players couldn’t have done it without them.”

Paul Brown, a fan who had driven down from Gladstone for the match and would later be CEO of London Broncos, reminisces: “I never FELT a grand final like it before or since. It was incredible.”

McGeoch left his wife to drive back with a newly-born child alone while he joined the players on the victorious bus journey, interrupted by at least four toilet stops. His own place in the sport’s folklore was assured - by accidentally puncturing someone’s lung while giving them a painkilling injection! “I used to feel really guilty about it,” the doctor says, before naming two rival club doctors who committed the same error with key player

Super League lawyer David Gallop, who would lead a united competition in years to come, was sitting at home watching on television. He says he just shook his head in astonishment at “an example of the game prevailing despite the politics around it. And I remembered those two occasions really clearly. One, at the Tri-Series (final) and the other, the 1997 ARL grand final and at the end of it thinking ‘wow, the game’s done it again’. It’s shown us all that it’s such a survivor.”

Hill: “My memory of the aftermath of it is that I’d never been involved in mass hysteria before. That’s how I viewed the crowd. They were hysterical because their wildest dreams had been fulfilled.

“I suppose that’s my answer to whether it was building. Not for any of us. It was just a complete shock.”

Keeble: “The celebrations afterwards have become part of town folklore. Chief, the Johns boys, Tony Butterfield, Marc Glanville … anyone who is ever interviewed about it talks about people lining the streets when they left the day before and then the long trip home … people lining the streets 50, 60 kms out of Newcastle and the slow crawl from the Wallsend roundabout into the Workers Club.”

Glanville: “We got to the two Shell servos at Wallsend there and we had a police escort by then. We pulled up at the lights and Matty and Joey got out and they’re up on top of the police car dancing and people are all cheering.

“It took us an hour to get from Wallsend into the Worker’s Club in King Street.

“The Sunday night was massive. I got a lift home from someone and had an hour’s sleep and then I went back in and we had Mad Monday. Tuesday we had the ticker tape parade. I had a spell Wednesday and then Thursday we were back on it.

“We went out to Cessnock and did the coalfields areas, a bit of a pub crawl.

“There was strong talk we wanted to go down to Manly and do a pub crawl. Luckily, we didn’t.”

Brett Keeble adds: “Most people seem to think that game and that result were the beginning of the end of the Super League War - and it seemed to play out that way.”

Paul Kind has thought a lot about that day in the quarter-century since.

“Fans on both sides just lost the sense of belief that their team was competing against the best other teams because you had that split comp,” he says. “I think that Manly-Newcastle grand final was really important because what it did at the end of that season was put it back together … no matter which side of the divide you were on, if you didn’t enjoy that grand final, I’d be surprised.

“If you were a Raiders fan or a Broncos fan or you worked at Super League, if you loved the game of rugby league that was a super-important game because it helped what was to come.”

McGeoch: “The grand final reminded people how great the game could be and what it was all about. It was about a working class town rather than the glitzy teams winning it.”

The only fan base that wasn’t willing to quietly let rugby league slide from the centre of Australian popular culture had been serendipitously blessed by a once-in-a-generation, transcendent moment.

And as Harragon will explain in the afterword, the team had been blessed and enabled by them. It was the nobility of the proletariat, writ large.

As they lined the streets leading into Newcastle and mobbed the players who partied with local heroes silverchair and the Screaming Jets, the people reclaimed The People’s Game before our eyes. Without this one match, reckons Dunstan, “the game wasn’t going to recover”.

Neil Whittaker’s eyes widen just a little at the memory: “Newcastle winning the comp, in an absolute blockbuster grand final, was the absolute turning point for us.

“I arranged with Channel Nine to be interviewed immediately after the game on the field and I invited all of the Super League teams to join our comp next year.

“And I told everybody that our 12 teams would be playing in the comp next year. I said ‘you should go have an off-season, don’t worry about the game, we’ll all be playing again next year’.

“And Frykers rang me the next day. ‘Let’s get started’.

“In my view, It’s the game that saved rugby league.”